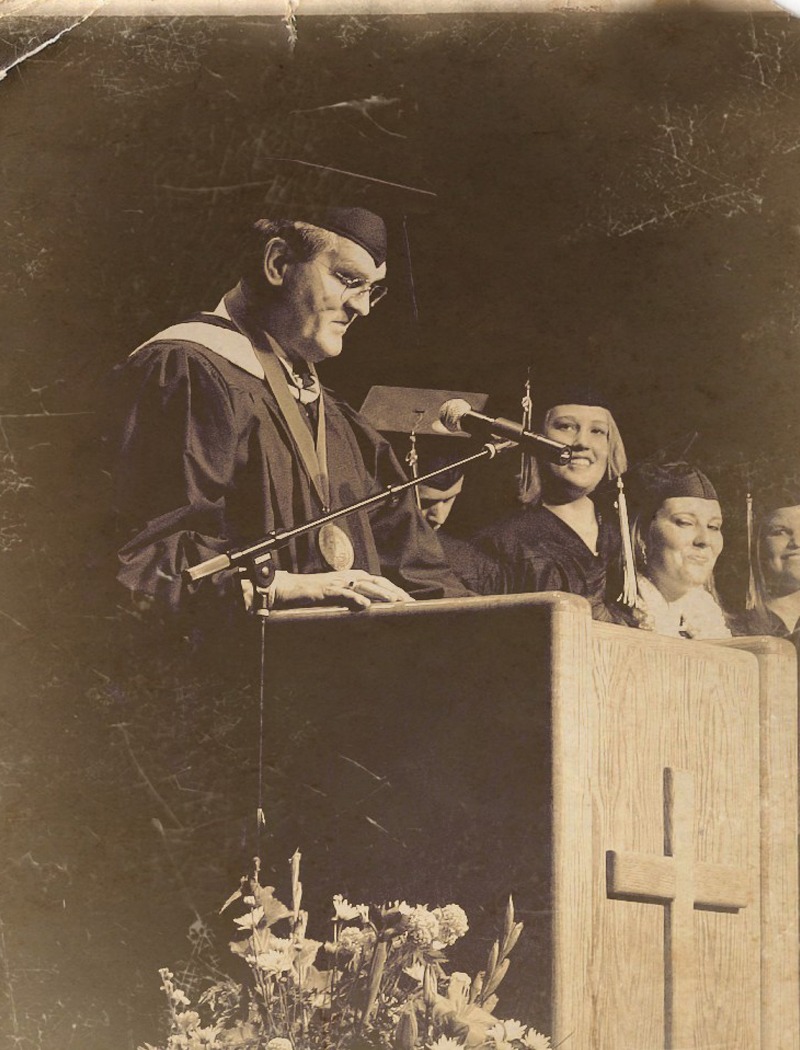

Dr. David Corbin’s commencement address to the Class of 2018

On an overcast day twenty-five years ago on the campus of the University of New Hampshire, Pulitzer Prize winning historian David McCullough delivered a commencement address to over 2,000 graduates. A member of that 1993 graduating class, I was not in attendance.

My choice would have been otherwise unnoteworthy had it not been to the great frustration of my father who, when I relayed my plans not to attend the ceremony the night before, replied:

My choice would have been otherwise unnoteworthy had it not been to the great frustration of my father who, when I relayed my plans not to attend the ceremony the night before, replied:

“How could you do this to your family, David? Don’t you realize how important this is to us?”

His were not the complaints of a parent angered because I was the first in my family to graduate from college. My father was upset because I had come from a family of college graduates.

As a family, we had never been wealthy, prominent, or influential. Yet, he explained that we took things like commencement ceremonies seriously because they represented the only consistent markers of accomplishment for a family that had otherwise achieved very little.

But I didn’t budge. I didn’t go the next day. He attended in my place, grabbed an extra program that he gruffly gave me weeks later, still angered by my uncaring decision not to attend. I’m not sure if he was ever more upset with me than that weekend. Of all the interactions that produced intense regret when years later, he passed away unexpectedly, that was the interaction that played over and over again in my head.

Regret doesn’t flow easily at 21, if at all. Not because I thought David McCullough had nothing important to say. But because I reasoned that the whole fuss associated with ceremonies was of little value, that what was truly important in college was what took place in the classroom or in the library when no one was looking. I still in part carry this idea with me, and never quite have enjoyed commencement ceremonies for that reason, never mind that they always seem to fall on warm days in May on my wife’s birthday, the academic garb weighs a ton, and I tend to perspire easily.

Yet, at the time, I was certain that my bias against ceremony amounted to a solid indictment against appearances for the sake of appearances. An aspiring Shakespeare scholar, I could cite Henry V’s famous critique of ceremony before the Battle of Agincourt to give my position that much more intellectual heft:

“And what have kings,

that privates have not too,

Save ceremony,

save general ceremony?

And what art thou,

thou idle ceremony?

What kind of god art thou,

that suffer’st more

Of mortal griefs than

do thy worshippers?”

(Henry V, Act IV, Scene i)

Here, King Henry ponders fame the night before he famously leads an overmatched army of Englishmen into France to do battle. What makes his speech so striking is that it is delivered by a man who had made an art form of employing appearances as a young prince to make his own life a spectacle, picturing himself as a sun that he would purposefully allow to be smothered by clouds, only so his radiant reappearance would bedazzle onlookers. King Henry learnt only later in life that a life lived to gain recognition from others is an unhappy life, not worth the sleepless nights and restless days.

And therein is the rub. So much of what we do in this age of images tends to turn on gaining the recognition of others. I was right as a young man to notice this and to skeptically reject idle ceremony as a foolish idol.

But I applied this judgment improperly in the case of my college commencement as I assumed the impersonal setting (sitting in a crowd of over 10,000 people) of the celebration signified that the whole affair

was impersonal. It wasn’t impersonal to my father. And your ceremony is not impersonal to you and your friends and family this morning.

Yet, had I gone to my own ceremony, I would have had to sit through a number of speeches that I thought had nothing to do with me. And given that I was the most important person to me that day, and most other days for that matter, I didn’t want to attend an event where I was lost in the crowd, even if it meant upsetting those close to me.

Perhaps one of the hardest things to learn in life is to gain joy from another’s enjoyment, especially when you believe that this costs something to you, whether it’s lack of attention when it’s showered on the other person, sacrifices we make that we think have gone unnoticed by others, the suspicious feeling that others are all take and no give, or simply the nagging question, “why you and not me?”, “why them and not us?”, in a sentence, our human tendency to view the seeming happiness that comes from importance as a zero-sum game.

Which brings me back to David McCullough. Fortunately for me, Mr. McCullough continued to make many commencement addresses over the years. So many that, last year, he put some of his best into an anthology titled, The American Spirit: Who We Are and What We Stand For.

I imagine had I been in the audience 25 years ago willing to listen to what McCullough had to say, I would have heard some of the many excellent admonitions that fill the pages of this volume. Some of the most memorable include the precepts that “History is human. It is about people, and they speak to us across the years,” “Nothing happens in isolation,” and “Everything that happens has consequences.”

Had I been there, I might have heard Mr. McCullough bring these precepts together in his praise of Dr. Benjamin Rush, a lesser known Founding Father, of whom John Adams once wrote: “I know of no character living or dead who has done more real good in America.”

In an excerpt that captures this sentiment perfectly, McCullough reads the diary of a Philadelphia woman named Elizabeth Drinker, a Quaker wife and mother whose large household included two free black children, boys aged seven and eleven, who to her alarm had taken severely ill.

Mrs. Drinker notes:

“Dr. Rush called,” she recorded April 8, 1794. “Dr. Rush here in forenoon…[despite] roads being so very bad” reads here entry for April 9. Dr. Rush called again on April 12, April 14, April 15, 17, 22, and 27, and on into the first week in May…He made fifteen house calls on those two boys by the time they were out of the woods.

Here, McCullough takes a set of dates, people, and places that easily could have been forgotten as numbers and letters on a page – just like “Providence Christian College,” “May 5, 2018” and “Pasadena, California” and reminds us that history is a human story; that these people were real; that they faced challenges, and during some of those challenges, they rose to the occasion and showed humanity at its best. In the best scenarios, heroes, like Benjamin Rush and Elizabeth Drinker, live not to gain recognition or to make history, but to live well.

At this point I may be risking crossing the line into the boilerplate address. Self-deprecation, check. Altruistic corrective, check. Perhaps all that is needed is a salute to all of you for your accomplishments and a call to arms as you move forward in life. Well, I’m not going to make it that easy because you and I know that it isn’t that easy.

There is still the elephant in the room… us. In other words, why can’t we get this thing right?

Perhaps the most celebrated recent commencement address, David Foster Wallace’s 2005 Kenyon College speech titled “This is Water,” takes up this question poignantly. Wallace begins his speech by telling a “parable-ish story.”

There are these two young fish swimming along and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says, “Morning, boys. How’s the water?” And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes, “What the hell is water?”

Wallace relates that because if we don’t think about water [“day in-day out” existence] the right way if at all, we end up self-centered, close-minded, bored, annoyed with others and unaware of what is real and essential: “capital-T Truth is about life before death.”

Closing his address with the words “this is water,” “this is water,” he wishes the young graduates “way more than luck.”

Tragically, Wallace would take his own life two years later.

In an autobiographical moment in his last published work, The Pale King, Wallace describes the struggle of a person who knows the difference between right and wrong and cares about the world he lives in, yet cannot face an existence he finds meaningless in the context of a “capital-T truth” that accounts for life both before and after death; the haunting feeling in Wallace’s words:

“That everything is on fire, slow fire, and we’re all less than a million breaths away from an oblivion more total than we can bring ourselves to even try to imagine.” Here Wallace gives us a picture of water [or existence] that is a living hell.

While Wallace bravely tried to encourage others in his literary career to account for their existence, perhaps he showed that the increasingly greatest challenge in life in the modern world is not overcoming one’s self-centeredness, or loving one’s neighbor, but struggling with doubt about why we’re here and whether we matter.

In other words, contemporary living is often like inhabiting a house divided against itself as we’ve been so trained to think of our existence in material terms that we doubt whether anything other than our material existence matters. And all along our soul longs for an eternal reality that seems beyond our reach.

This may not be you today. But you will have days like this in the future when you thirst for more than what this world with all of its material enjoyments has to offer you; when no matter how hard you try to be cognizant about your own shortcomings or forgive the shortcomings of others, life will feel like a dry and desolate wilderness.

Feeling divided and getting lost in such a wilderness begs an answer to the map of history Lincoln famously introduces in his “House Divided” speech. “If we could first know where we are, and whither we are tending, we could then better judge what to do, and how to do it.”

“Where we are?” is a matter of knowing who God is and who we are. Consider the

parable of the Samaritan woman in John’s gospel in our scripture reading for this

morning:

When a Samaritan woman came to draw water, Jesus said to her, “Will you give me a drink?” (His disciples had gone into town to buy food.)

The Samaritan woman said to him “You are a Jew and I am a Samaritan woman. How can you ask me for a drink?” (For Jews do not associate with Samaritans.)

Jesus answered her, “If you knew the gift of God and who it is that asks you for a drink, you would have asked him and hewould have given you living water. (John4: 7-10)

Jesus teaches the Samaritan woman and us who He is, who we are, and what we can ask of Him; that the living water received by those who believe in Him will produce a spring of water that wells up in our souls and replenishes and nourishes us eternally.

“Whither we tend?” is the story of His creation, our rebellion, His love, and our hoped-for redemption and eternal salvation.

“What to do and how to do it” certainly will be made difficult by our own selfcenteredness. It will be hindered by human dysfunction. It will be challenged by living in an age where His nature and ours is denied. In a sentence, you will be tempted into believing, on the one hand, the lie that you are greater than Him and, on the other hand, the lie that you mean nothing to Him.

Yet, having attended Providence Christian, a college whose mission is “to equip [you] to remain firmly grounded in biblical truth; thoroughly educated in the liberal arts; and fully engaged in [your] church, [your] community, and the world for the glory of God and for service to humanity,” you will be better enabled to see these lies for what they are and to know that His is living water.

My hope and prayer for you in the years ahead is that your Providence education will have taught you to draw from His well daily, that it would have encouraged you to let rivers of His water flow within you, and that your story will amount to His water being poured out from you onto others for His everlasting glory.